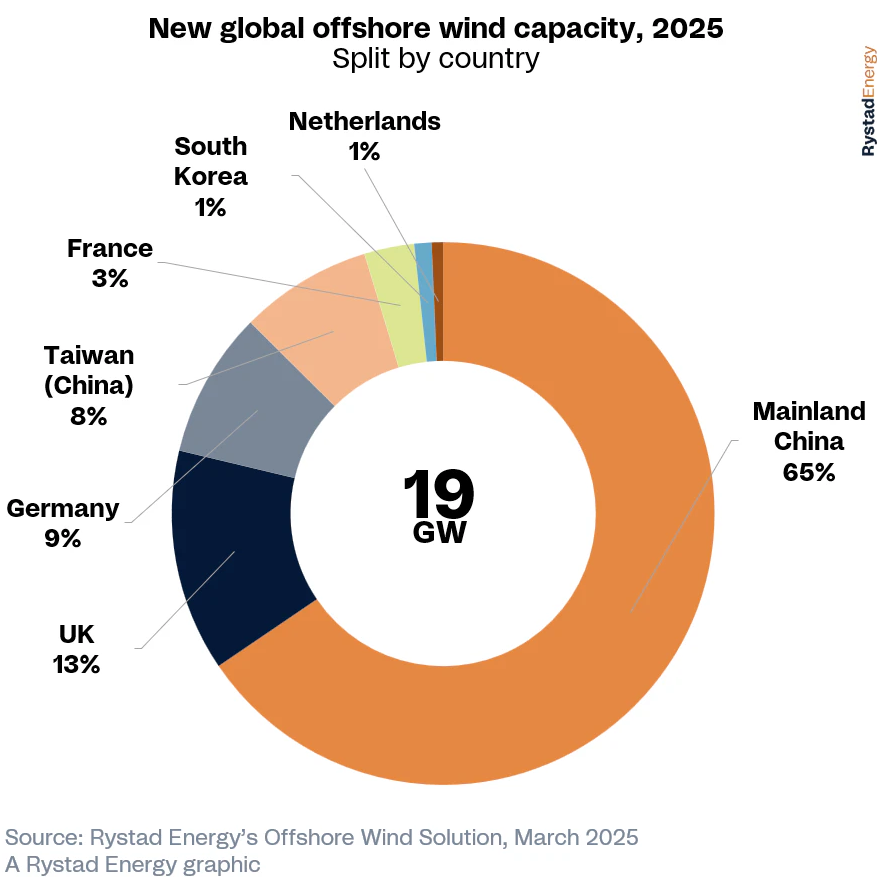

The global offshore wind industry is set for a strong rebound in 2025, with capacity additions forecast to reach 19 gigawatts and total sector investment projected to hit a record-breaking US$80 billion, according to research from Rystad Energy. This upswing follows a slowdown at the end of 2024, when new installations fell to around 8GW, down by 2GW from the previous year.

Asia-Pacific is now the main driver of global offshore wind growth. The region overtook Europe in cumulative offshore wind capacity in 2022, a trend the Global Wind Energy Council ( GWEC ) expects to continue through at least 2032.

Mainland China remains the world’s largest offshore wind market, accounting for a striking 65% of new global capacity in 2024, according to Rystad Energy. While China continues to lead, the broader APAC market is undergoing a shift towards diversification. Large-scale developments in markets such as China, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, and Australia are positioning the region as a future global hub for offshore wind innovation and deployment.

Localized supply chains

As countries in the region seek to maximize the economic and social benefits of energy transition, there is an increasing emphasis on building localized offshore wind supply chains. Many governments are adopting local content requirements ( LCRs ) to stimulate local job creation, industrial development, and technology transfer. While these policies are well-intentioned, GWEC cautions in its latest position paper that poorly designed or overly stringent LCRs can inadvertently raise project costs, deter foreign investment, and slow the pace of renewable energy deployment.

Taiwan stands out as a leader in the development of a non-China offshore wind supply chain, having attracted significant foreign investment and expertise over the past few years. Previously, Taiwan’s Industrial Relevance Programme ( IRP ) required offshore wind developers to use a certain percentage of locally manufactured components, which some argued could violate World Trade Organization ( WTO ) rules. However, in November 2024, the Taiwanese government relaxed these requirements, shifting its focus from localization to grid connection.

The most high-profile offshore wind deal in the APAC region in 2024 was the US$1.6 billion project financing for the 583MW Greater Changhua 4 offshore wind farm in Taiwan. The project reached financial close on December 12, 2024. It forms part of the 920MW Greater Changhua 2b and 4 offshore wind farms, which Ørsted is currently constructing and expects to complete by the end of 2025. Following Cathay Life's investment, Greater Changua 4 will be co-owned by Ørsted and Cathay Life Insurance, with each holding a 50% ownership stake. The project represents the largest investment made by a Taiwanese life insurer in an offshore wind farm to date.

Offshore wind turbine manufacturing is currently dominated by a mix of European, American, and Chinese suppliers. According to Blackridge Research & Consulting, the world’s top manufacturers in the field are Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy ( Spain ), Vestas ( Denmark ), and GE Vernova ( US ). Six of the top 10 offshore wind turbine manufacturers are from China – Goldwind, Envision Energy, Mingyang Smart Energy, Shanghai Electric, Dongfang Electric, and CSSC Haizhuang. South Korea is represented by Doosan Heavy Industries, which has been increasingly active in both domestic and international markets. These manufacturers not only lead in turbine production but also influence the development of broader supply chain ecosystems, including nacelle assembly, blade production, and offshore substation equipment.

The surging cost of offshore wind projects is a major concern. Rising material costs have affected financing and slowed growth. Ørsted recently canceled its UK offshore wind project, Hornsea 4, citing soaring supply chain costs, higher interest rates, and increased project risk.

Emerging offshore wind markets

South Korea and Japan are making strides in replicating Taiwan’s success in offshore wind projects. In October 2024, South Korea’s Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy launched a tender to procure 1.8GW of wind power, including 1GW of fixed-bottom offshore wind, 500MW of floating offshore wind, and 300MW of onshore wind. Japan is expected to award new offshore wind contracts, with a focus on floating wind technology and grid integration.

Also, Vietnam and the Philippines are demonstrating strong potential, although challenges exist. In Vietnam, offshore wind projects can be pursued using either the independent power producer ( IPP ) model or the public-private partnership ( PPP ) framework. However, both investment structures are currently constrained by regulatory bottlenecks, limited institutional capacity, and a lack of clarity on policy implementation. The IPP framework is hindered by overlapping responsibilities among government entities and insufficient coordination at both the provincial and national levels. Although recent legislation has sought to address issues concerning the bidding process, offshore wind remains excluded from its scope. As a result, developers are left navigating a complex and opaque system, which continues to deter investment and delay project timelines, according to the CWEC report.

The Philippines has taken more decisive early steps to prepare for offshore wind deployment. The country enjoys natural advantages such as a strong maritime industry, skilled labour, and access to key minerals needed for clean energy technologies. In addition, the government has played an active role in enabling project development. In 2023, the administration of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr issued Executive Order 21 to streamline permits for offshore wind projects, and released the omnibus guidelines standardizing procedures for awarding wind energy contracts. Further progress was made in October 2024, when the Department of Energy and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources signed a memorandum of agreement granting developers access to offshore areas and auxiliary zones under official service contracts. These measures aim to fast-track project approvals and reduce early-stage uncertainty for investors.

Nonetheless, policy refinement is necessary if the Philippines is to fully realize its potential. While most early offshore wind projects will rely on imported technologies and expertise, there is a growing opportunity to localize specific parts of the supply chain over time. According to GWEC, focused investment in workforce development, component manufacturing, and port infrastructure would enable the country to gradually build a domestic offshore wind ecosystem that supports long-term growth and energy security.

Emerging technologies such as floating offshore wind turbines are expected to play a transformative role in the coming years. Unlike fixed-bottom structures, floating turbines can be deployed in deeper waters, unlocking vast new areas for development. Projects like the Kuji Floating Wind Farm in Japan show the innovation expanding project viability in regions with limited shallow sea beds, including parts of Southeast Asia.